This post by Duncan McDonnell originally appeared at LSE's EUROPP blog.

Here’s a shocking statistic: after the 2012 local elections, not one of Italy’s 50 (yes, fifty) largest cities will have a female mayor. Here’s a less shocking one: the Italian media seems not to have noticed. Rather, the focus of attention since the first round of local elections two weeks ago has been mostly on the results gained by comedian Beppe Grillo’s Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S – Five Star Movement) and on the poor performances of Silvio Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PDL – People of Freedom) and the Lega Nord (LN – Northern League). However, there is little reason for cheer for any of the parties currently in parliament.

Movimento Cinque Stelle leader Beppe Grillo Credit: Wikimedia Commons (BY SA)

Although the first round of local elections on May 6th and May 7th only concerned around 20% of the total electorate, it was inevitably seen as a first key test for the parties following the suspension of party government at national level and the installation of Mario Monti’s technocratic government in November 2011. As the results came in, there were three obvious conclusions. The first was that the bipolarization of politics which has long been touted as the remedy to Italy’s ills is now in tatters. In part this was due to the former allies PDL and LN running separately, but it also reflected a general fragmentation of the vote. Since the introduction of directly-elected mayors in 1993, Italy has had a local electoral system that turned most mayoral contests into two-horse races. Not any more. As Vincenzo Emanuele of CISE shows, while the top two mayoral candidates received an average total of 88% in the first round of the 2007 elections (when most of the same cities last voted), this has now fallen to 69%. The days of a straight centre-left versus centre-right fight are gone for now.

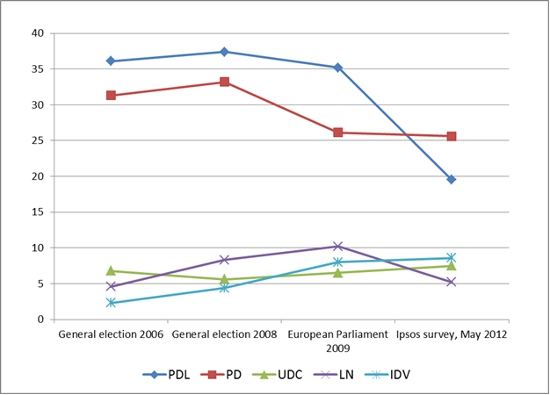

The second obvious conclusion was that the PDLand the Lega Nord did badly on all fronts: mayoral victories, council seats and overall vote share. As a study by the Istituto Cattaneo highlights, compared to the 2010 regional elections, both parties have lost at least half their votes in absolute terms. The story is not so rosy however for the other major parties, which have seen many of their voters abstain in 2012. The centre-left Partito Democratico (PD – Democratic Party) will finish up with more mayoralties, but this does not reflect a jump in popularity for it or the other two parties in national parliament, Italia dei Valori (IDV – Italy of Values) and the Unione di Centro (UDC – Union of the Centre). Rather, as an Ipsos survey conducted on 7 May showed, while the PD remains in first place, it does so with just over 25%. Indeed, as we can see from the figure below which compares current poll results with the last two general elections and the 2009 European Parliament elections, none of the current parties in parliament is benefiting particularly from the decline of the PDL and the Lega Nord.

Figure 1 – General and European election results in Italy since 2006, and current polling

Source: Ministero dell’Interno and Ipsos

So who is doing well? This brings us to the third obvious conclusion from these elections. Although Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S) had been rising in the polls for some time, its results took all commentators by surprise. In the north and centre-north, it received well over 10% of the vote and in cities like Genoaand Parma(where its mayoral candidate has made the second round), it performed way beyond expectations. Perhaps fuelled by this success, it is now running at between 12% and 17% in national opinion polls. There has been a widespread tendency to dismiss Grillo’s movement as ‘anti-political’. However, this does it a disservice. While it is certainly ‘anti’ the main parties, ‘anti’ the Monti government and ‘anti’ austerity, it is not anti-politics per se.

In fact, Grillo’s meet-ups and now the M5S have been active for at least five years at grassroots level in campaigns ranging from sustainable development to political transparency to utility privatizations. They are not saying that politics is a dirty world which voters should keep at arm’s length by delegating the M5S to sort it out. Rather, they are saying that the current parties are incompetent and untrustworthy and that citizens themselves should become more involved in scrutinizing and shaping decisions. Moreover, as an ISPO survey shows, over 30% of those who voted for the M5S two weeks ago had previously abstained. The movement is thus bringing people back into politics at a time when over 40% of respondents are stating in surveys that they are not planning to vote or are undecided. And when just 66.9% voted in the local elections – the lowest such turnout to date.

Finally, a less obvious conclusion: while a few years ago, Letizia Moratti was mayor inMilan, Marta Vincenzi in Genoa and Rosa Russo Iervolino in Naples, now none of Italy’s 50 largest cities has a female mayor. Amidst all the debate regarding Grillo and the state of the parties, this development seems to have gone unnoticed in Italy. Sadly, it is entirely in line with the composition of the country’s current governing class. Only two out of Italy’s twenty regions have a female president, while most Italian party leaders are male and over 60. Meanwhile, in the absence of the parties, the Monti technocratic government has provided some continuity at national level thanks to a cabinet with an average age of 64 and just three women ministers out of 18. The party system may be in turmoil, but Italy remains a country for old men. In that sense, but probably only that, the sprightly 63-year old Mr. Grillo fits right in.

Duncan McDonnell – European University Institute, Florence

Duncan McDonnell – European University Institute, Florence

Duncan McDonnell is Jean Monnet Fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre of the European University Institute in Florence. He is the co-editor of Twenty-First Century Populism (Palgrave, 2008) and has published recently on the Lega Nord and Outsider Parties. He is currently working with Daniele Albertazzi on a book entitled ‘Populists in Power’ (Routledge, 2013) and with Anna Bosco on the 2012 ‘Politica in Italia/Italian Politics’ yearbook, published in Italian and English by Il Mulino and Berghahn.